Home / Intelligence / Blog / Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: No Room for Negotiation

Published August 12, 2022

Long-awaited Medicare price negotiations look more like statutory discounts than the value-based negotiations seen in global healthcare systems; combined with expanded price increase rebates and out of pocket limits, new regulation may drive prices for new drugs up more than down. Trinity explores the impact and implications for manufacturers of innovative medicines.

Headline Summary:

- After over a year of drafting, Congress recently passed the Inflation Reduction Act, and on August 16th President Biden formally signed the act into law

- The act includes many significant changes for Medicare, including installing a $2,000 annual out of pocket spending limit for Medicare beneficiaries and mandating rebates for drugs if price increases exceed the rate of inflation

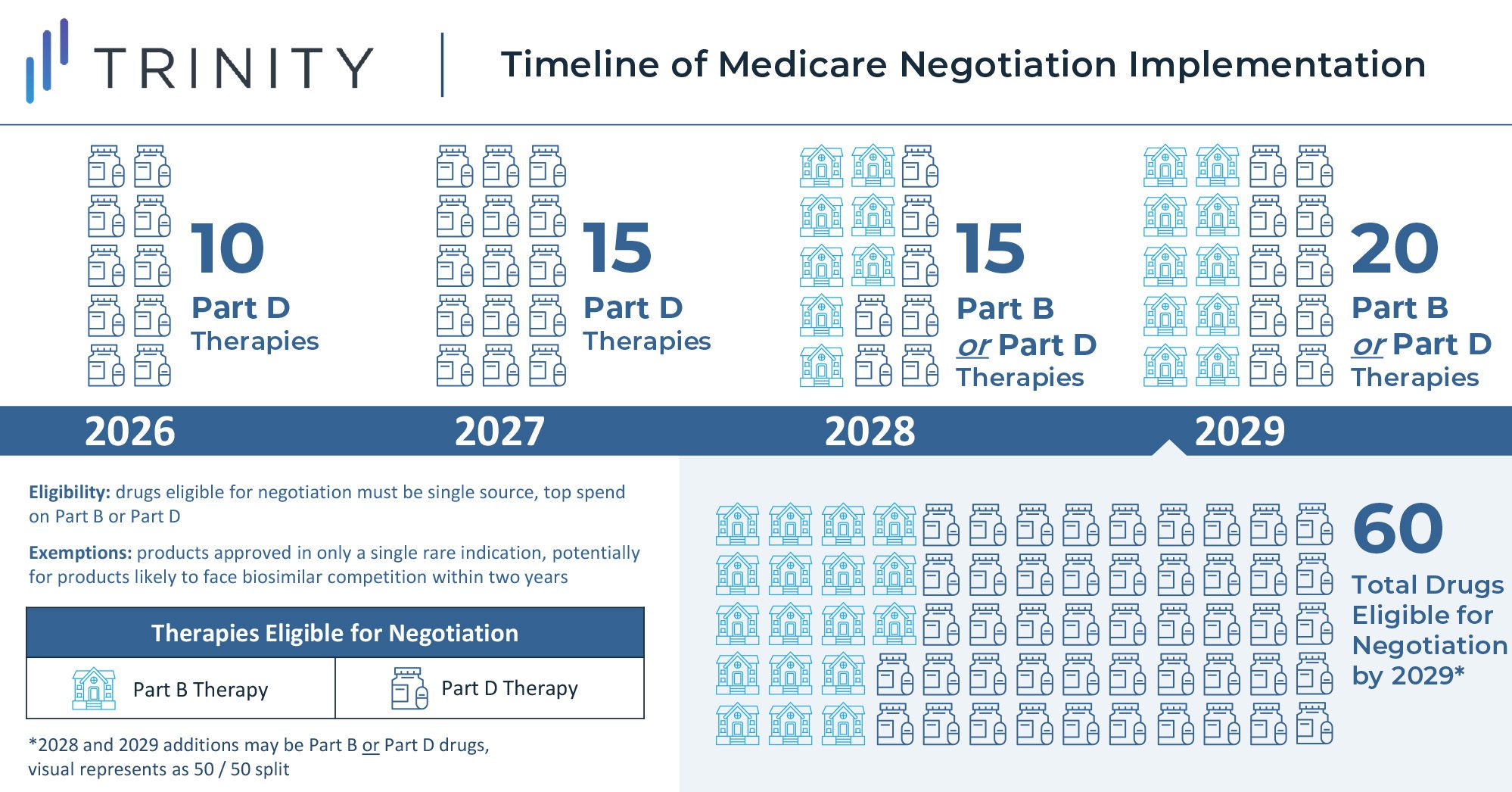

- Starting in 2026, top-selling Medicare drugs that have been on the market for close to or over a decade without generic or biosimilar competition will face minimum discounts of 25-60% that are subject to negotiation with the Secretary of Health and Human Services; as the law is currently written, this will start with 10 drugs in the first year and expand to 60 Part B and Part D drugs by 2029

Trinity’s Take:

- Through a series of discounting rules, the law functions to capture savings from blockbuster medicines that enjoy long-term success in the Medicare market rather than introducing government-manufacturer price-setting negotiations that have become the norm in many global markets

- Future blockbuster therapies treating diseases with a high share of Medicare patients will face revenue pressure late in the product lifecycle under the new rules, and earlier than they otherwise would have due to loss of exclusivity

- Reduced long-term revenue potential, combined with constraints around price increases and capped out of pocket spend in Medicare, may lead manufacturers to seek higher prices when launching new products given the price-setting freedom that remains untouched by the new legislation

Introduction

In a narrow vote, the Senate recently passed the Inflation Reduction Act through the budget reconciliation process with affirmative votes from all 50 Democrat senators and a tie-breaker decision from Vice President Harris. The House similarly voted in favor of the act along party lines, and on August 16th, President Biden signed the act into law.

While the law restructures many social programs, Medicare and the biopharma landscape are both heavily impacted. Medicare reform policies in the act are expected to reduce the federal budget deficit by $288 billion from 2022 to 2031, with an estimated $101.8 billion in Medicare savings as a result of the new drug price negotiation policy. The law includes rules for gradual implementation of key Medicare changes, so these projected savings will increase during this timeframe and are backloaded. The law also secured $64 billion to fund ACA state and federal exchange subsidies to avoid premium increases for 13 million Americans. These subsidies were previously financed through a COVID program set to expire in September 2022 and are now extended through 2025.

Medicare Direct Negotiation

One of the key features of the law grants the US government the ability to negotiate on behalf of Medicare for select medicines starting in 2026. However, the implementation is unlike negotiations seen in Europe and other global markets where manufacturers negotiate drug prices with governments near time of launch, and the law instead mandates minimum discounts for products late in their lifecycle. These discounts will be gradually expanded through 2029 and applied only to drugs meeting certain criteria (i.e., drugs with the highest total cost to Medicare with no generic or biosimilar competition). Implementation of the rule will begin in 2023, with discounts taking effect for 10 Part D drugs in 2026 and for 15 additional Part D drugs in 2027. Starting in 2028, discounts will apply to eligible drugs across Part B and Part D, resulting in a total basket of 60 eligible discounted Part B and Part D drugs in 2029.

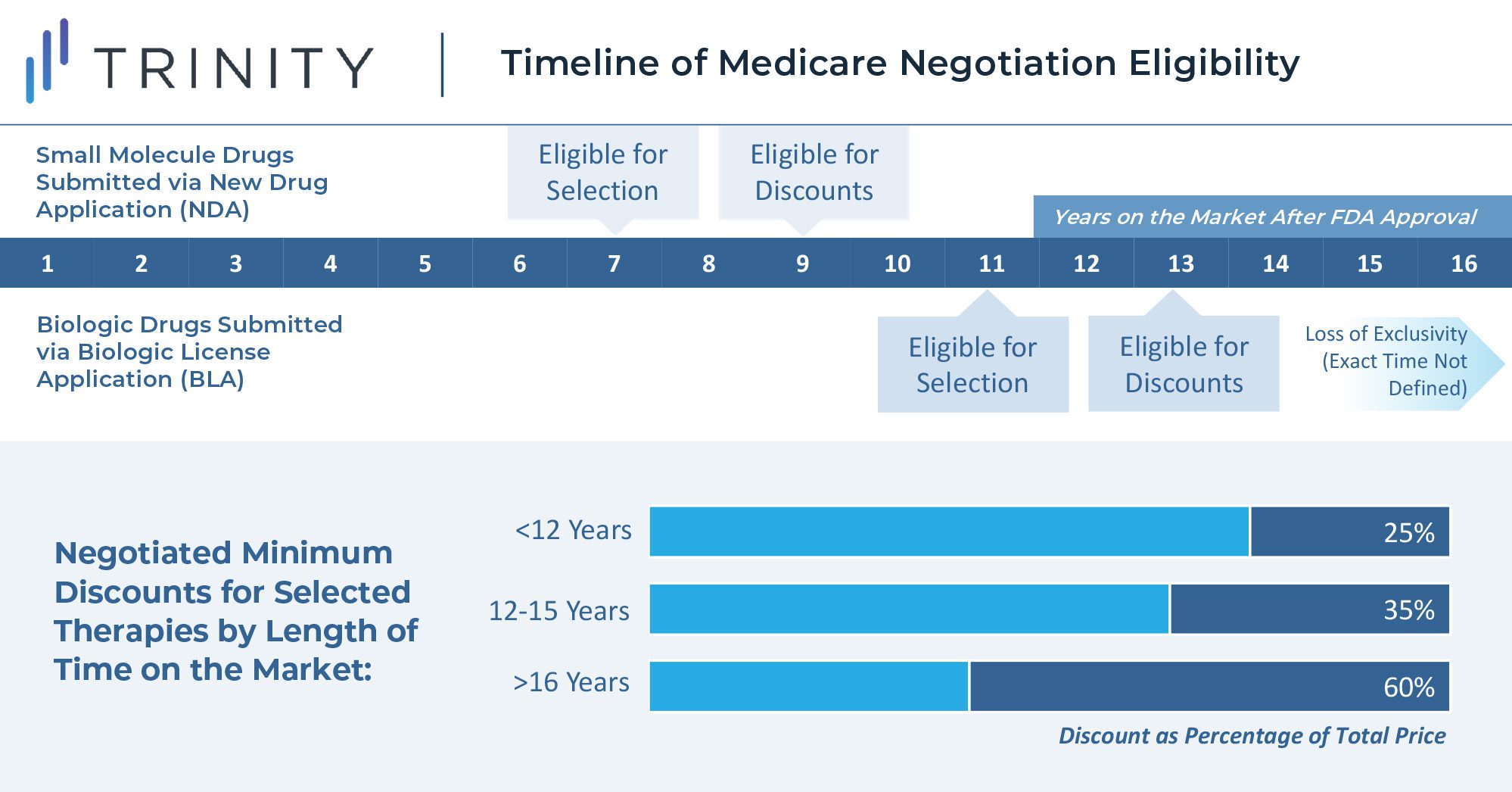

The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services is tasked with selecting drugs that drive the highest cost to Medicare and are on the market past original exclusivity without generic or biosimilar competition. Additionally, the act specifies that small molecule drugs are eligible for negotiation 7 years after FDA approval, and biologics are eligible for negotiations 11 years after FDA approval. Discounts for eligible drugs will start two years later. The act will first impact Part D covered drugs that incur the highest Medicare expenditure. In 2020, the top ten therapies in Medicare spend included blood thinners, oncology treatments, diabetes treatments, immunology therapies, and asthma treatments. Notably, plasma-derived therapies and orphan therapies with a single indication are excluded from eligibility.

The minimum discounts are determined by how long the therapy has been available on the market. Selected products will be required to provide a 25% minimum discount if on the market for less than 12 years. Products on the market between 12 and 15 years will be discounted by at least 35%, and products on the market for longer than 16 years will be discounted by at least 60%. While these discounts apply only to Medicare, it seems likely that commercial insurers will use these as a basis to extract their own price concessions, introducing further uncertainties to the scale of these discounts.

Maximum discounts are not quantitatively defined in the legislation, but the steep minimum discounts leave manufacturers with little room for a true negotiation. When setting the discount level above the minimum, the law instructs the Secretary to consider manufacturer-specific data, including research and development costs, cost of production and distribution per unit, prior federal financial support for the discovery and development of the drug, pending and approved patent applications, and market, sales, and volume data for the drug in the United States. This wide-encompassing imperative seems to leave much of the interpretation of the rule to the incumbent Secretary and will thus likely be one of the most challenging components of the legislation to put into practice.

In any respective year for a selected drug, the law requires the manufacturer to provide all information listed above to inform the maximum discount by March 1st, and the Secretary must share an initial maximum fair price of the drug with written justification by June 1st. Within a month, the manufacturer must either accept this maximum fair price or share a counteroffer. This process can repeat, but all negotiations between the Secretary and manufacturer must complete by November 1st.

The legislation also sets penalties to ensure the minimum discount negotiation is implemented. Non-compliant manufacturers will be excise taxed on their gross revenue: 65% in Q1 of noncompliance, 75% in Q2, 85% in Q3, and 95% in Q4. With limited details on how a maximum discount may be set, many biopharma researchers and manufacturers have opposed the law and the proposed minimum price cuts, citing their lack of negotiation power in the process and harsh penalties of non-cooperation. As the legislation moves into the implementation phase, legal challenges are almost certain to arise.

Price Increase Regulations

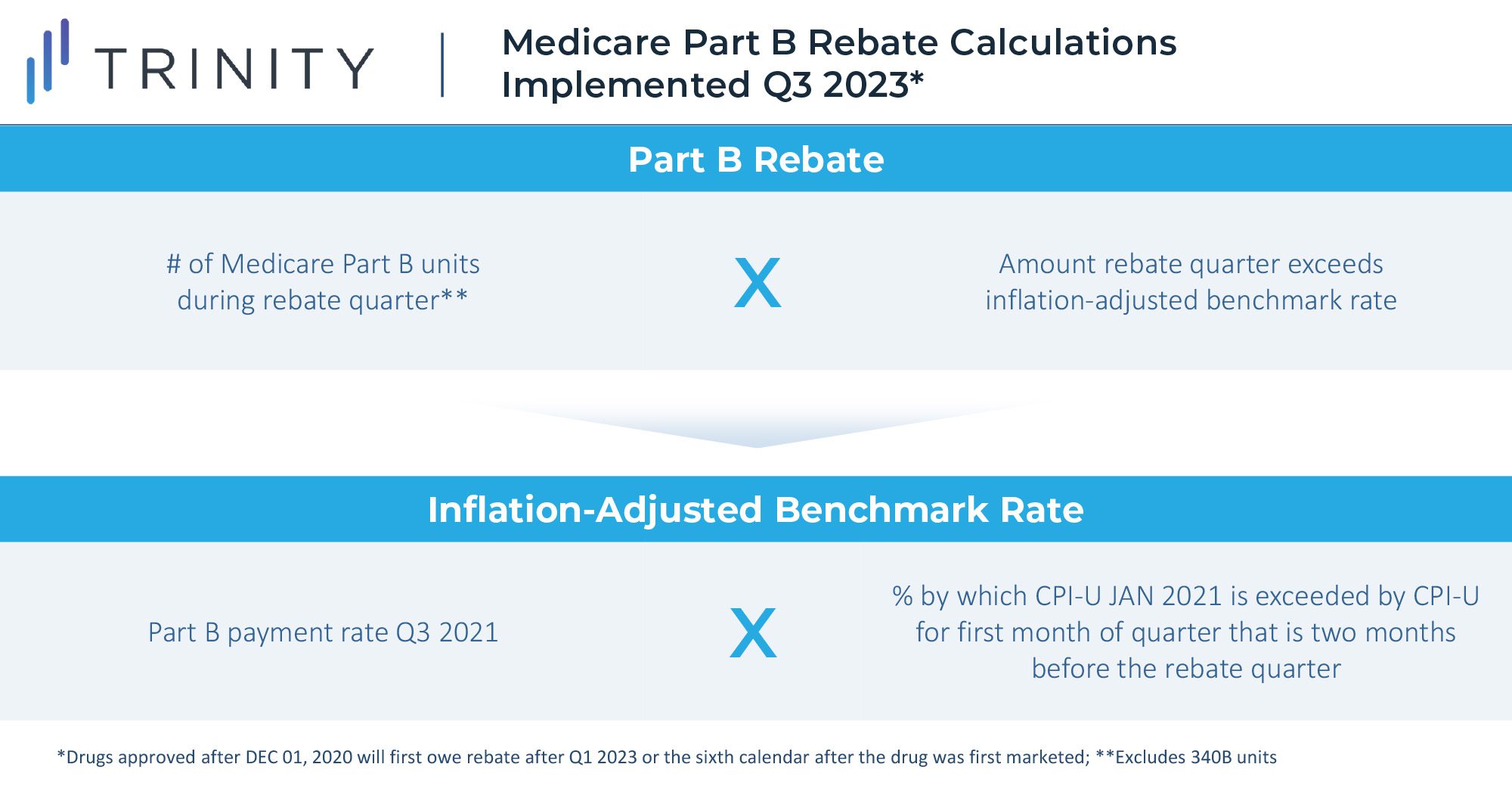

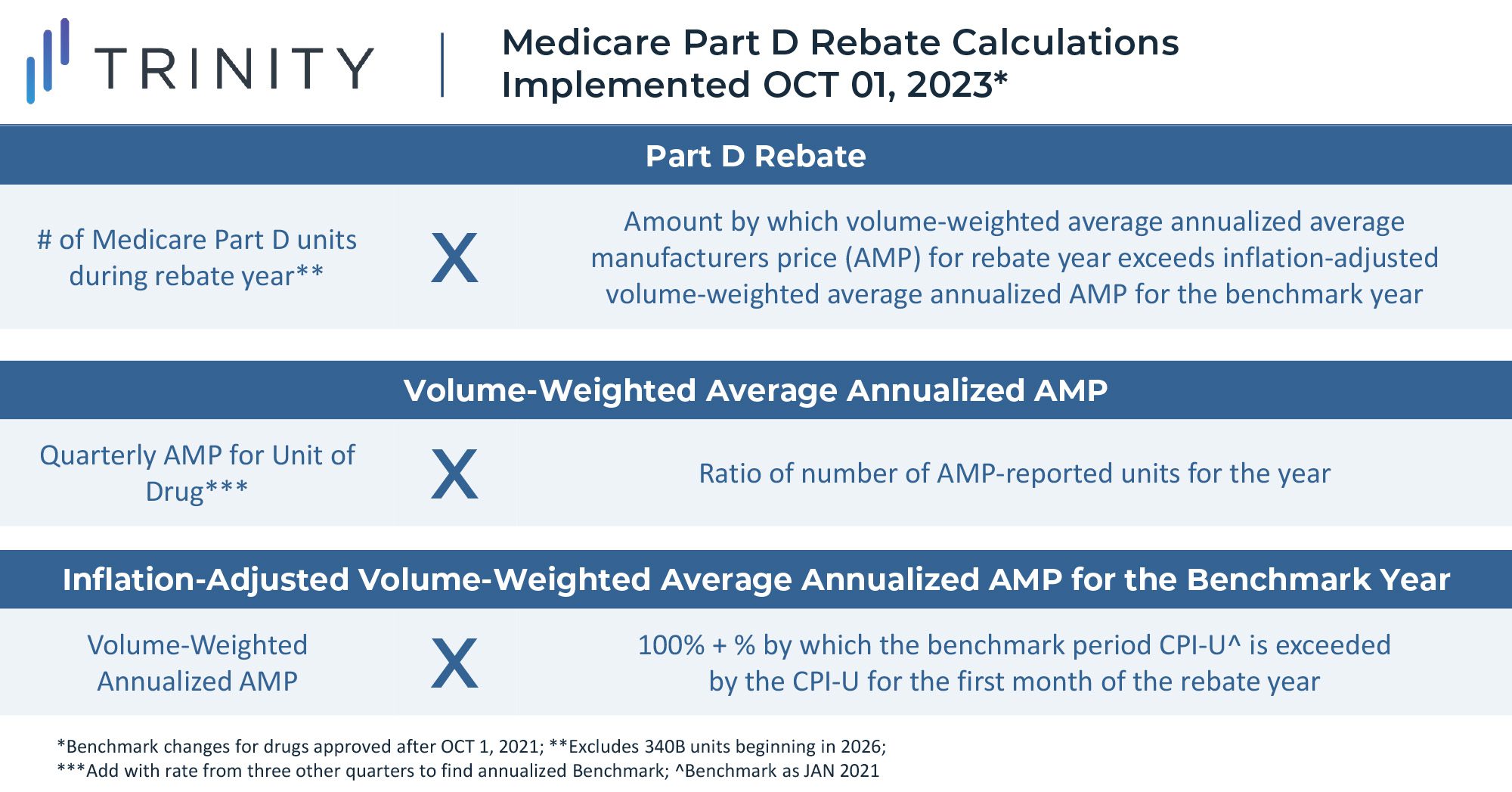

Starting in October 2022 for Part B drugs and April 2023 for Part D Drugs, biopharma companies will be required to pay rebates to Medicare if increases in their drug prices surpass the rate of inflation for the preceding quarter. Rebates will be limited to sales in the Medicare channel, as the Senate Parliamentarian struck down an initial proposal to implement the rebates for both Medicare and commercial units. The goal of the rule is to reduce the rate of price increases and to provide further savings for Medicare.

Part B drugs that will be subject to rebates include single source drugs, biologics, and biosimilar products; exceptions include vaccines and low Medicare spend drugs. Part D drugs subject to rebates include drugs or biologics funded under Part D and exclude low Medicare spend drugs.

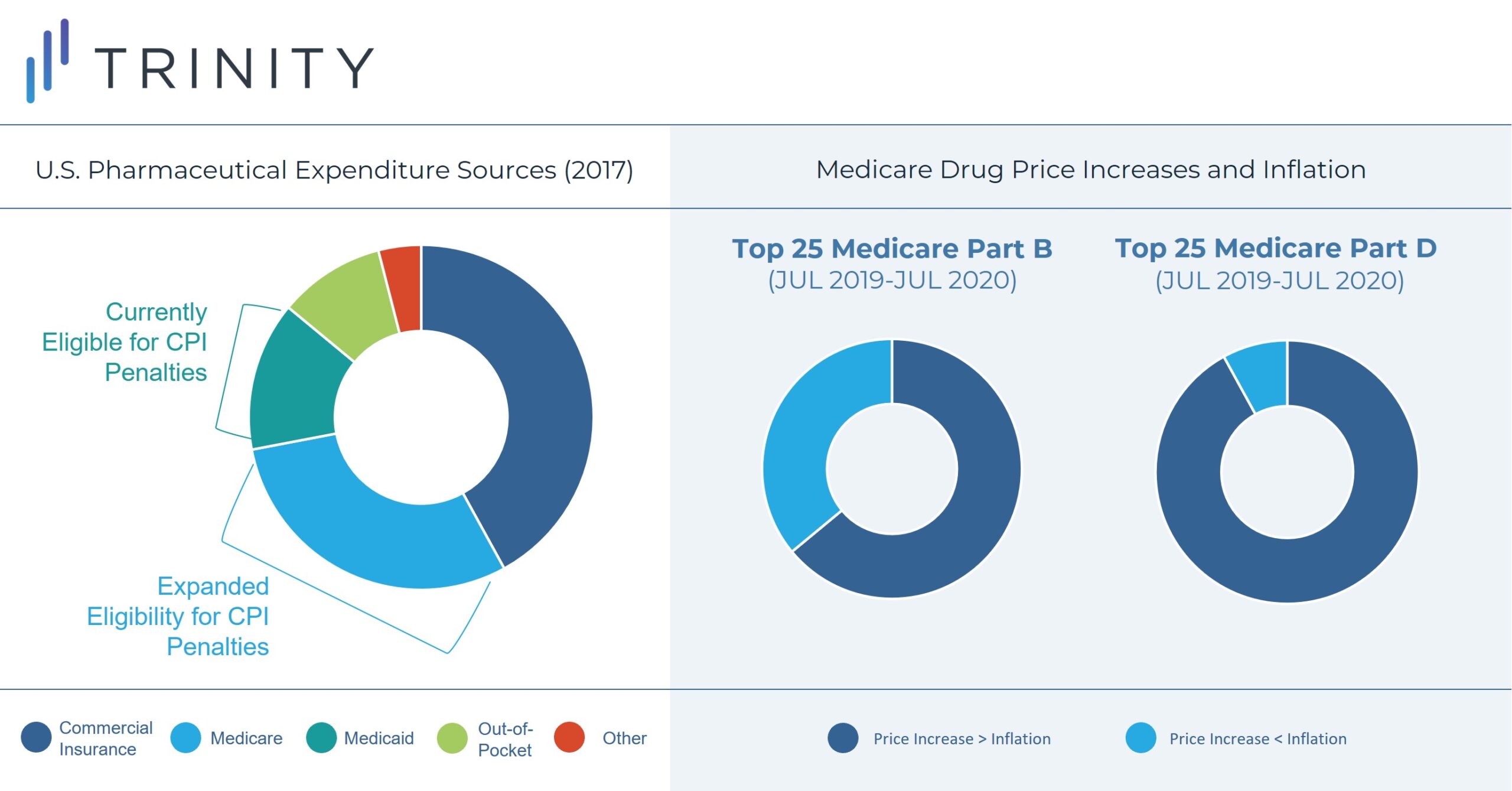

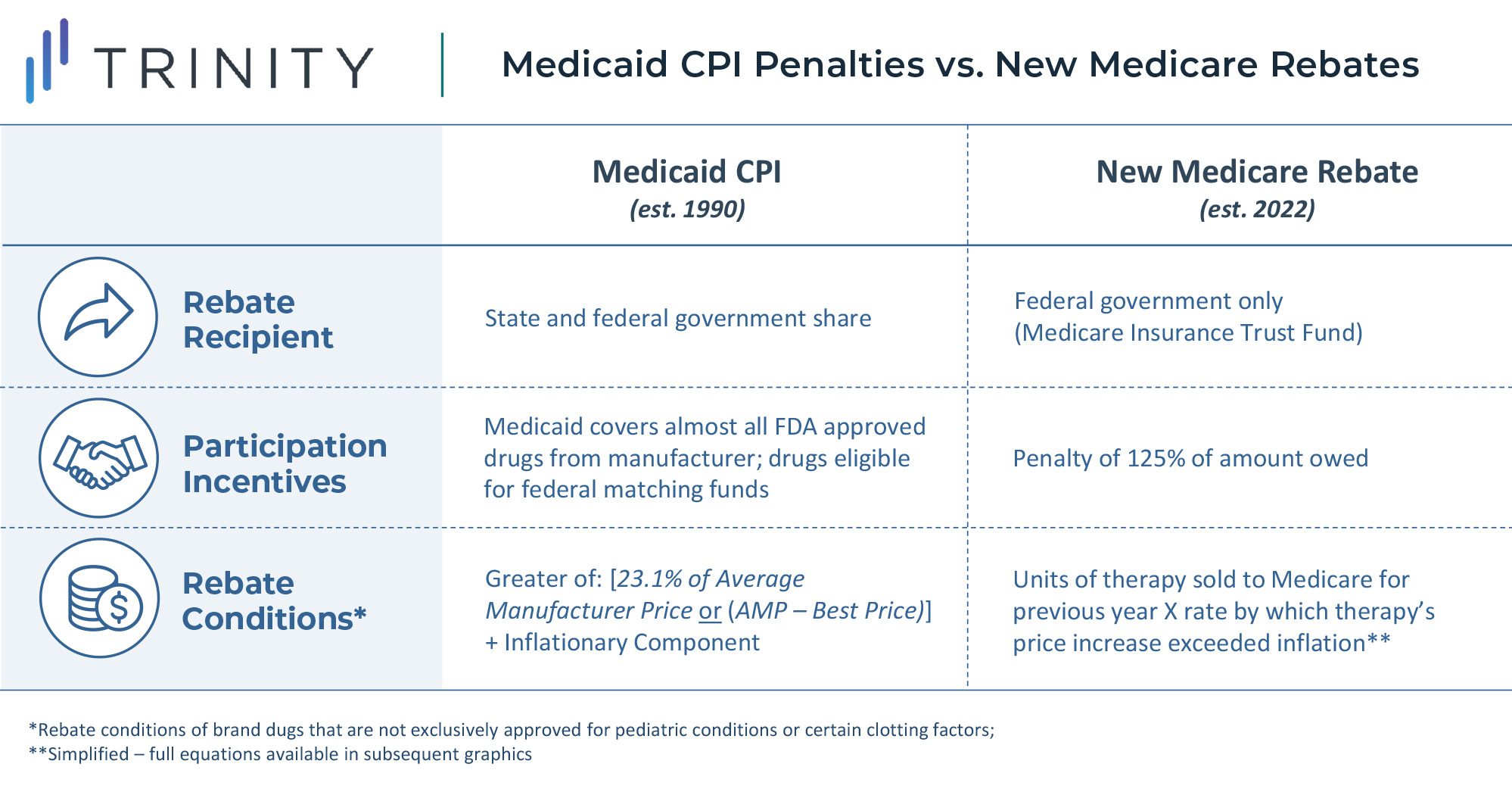

This rebate rule is similar to an existing Medicaid Consumer Price Index (CPI) penalty. However, this will likely be more impactful to manufacturer profitability due to the larger share of Medicare revenue for most products. Notably, a constrained and uncertain price increase environment will put more emphasis on launch pricing decisions and will potentially lead manufacturers to be more aggressive on pricing for new assets launching in the future. Penalties for price increases beyond inflation are likely to be highly impactful constraints even without the inclusion of commercial sales in the rebate calculation. While foregoing revenue in Medicaid may be acceptable for products today due to the CPI-U penalty, doing so for Medicare and Medicaid is likely prohibitive.

Between July 2019 and July 2020, the prices of 1,947 Medicare drugs, distributed evenly between Part B and Part D, increased at a rate higher than inflation. Among this group, 668 drugs had price increases of 7.5% or more. Additionally, 23 of 25 of the top Part D drugs and 16 of 25 top Part B drugs experienced price increases exceeding inflation. Notably, inflation was 1% annualized during 2020 compared to 9% in June 2022.

Medicare Part D Out of Pocket Cap

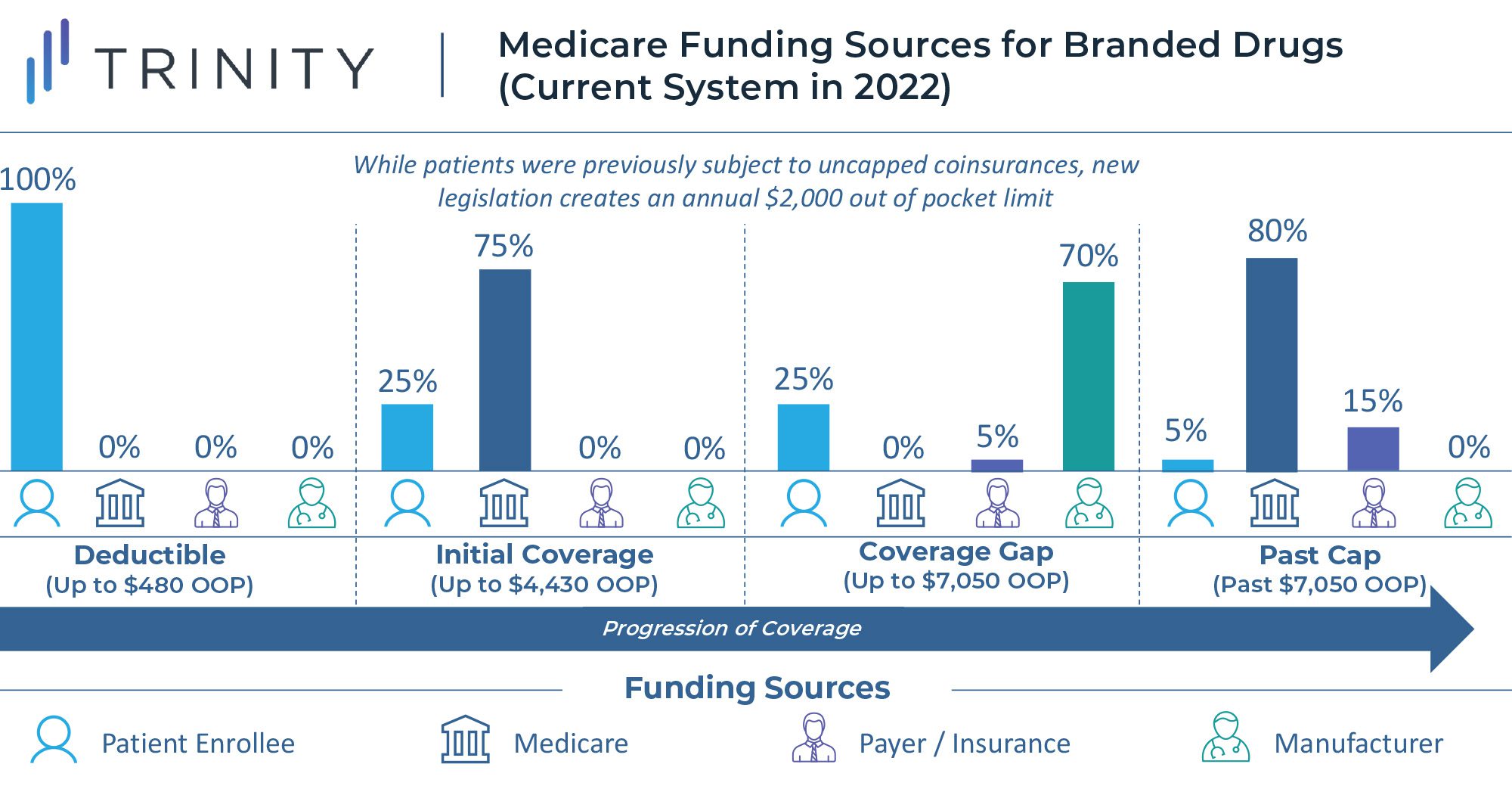

Another major component of the reforms to the Medicare program is the implementation of an annual out of pocket cap for Medicare Part D beneficiaries who do not already qualify for the “low-income subsidy” program. Currently there is no out of pocket ceiling for Medicare Part D, and enrollees hit catastrophic coverage with a 5% coinsurance once they exceed $7,050 in annual spending on medications. Once a beneficiary enters catastrophic coverage, they are required to pay 5% of the drug cost out of pocket, with the remainder of costs covered, 80% by Medicare and 15% by the health plan. This methodology can drive a significant cost burden for Medicare members with chronic, high-cost conditions.

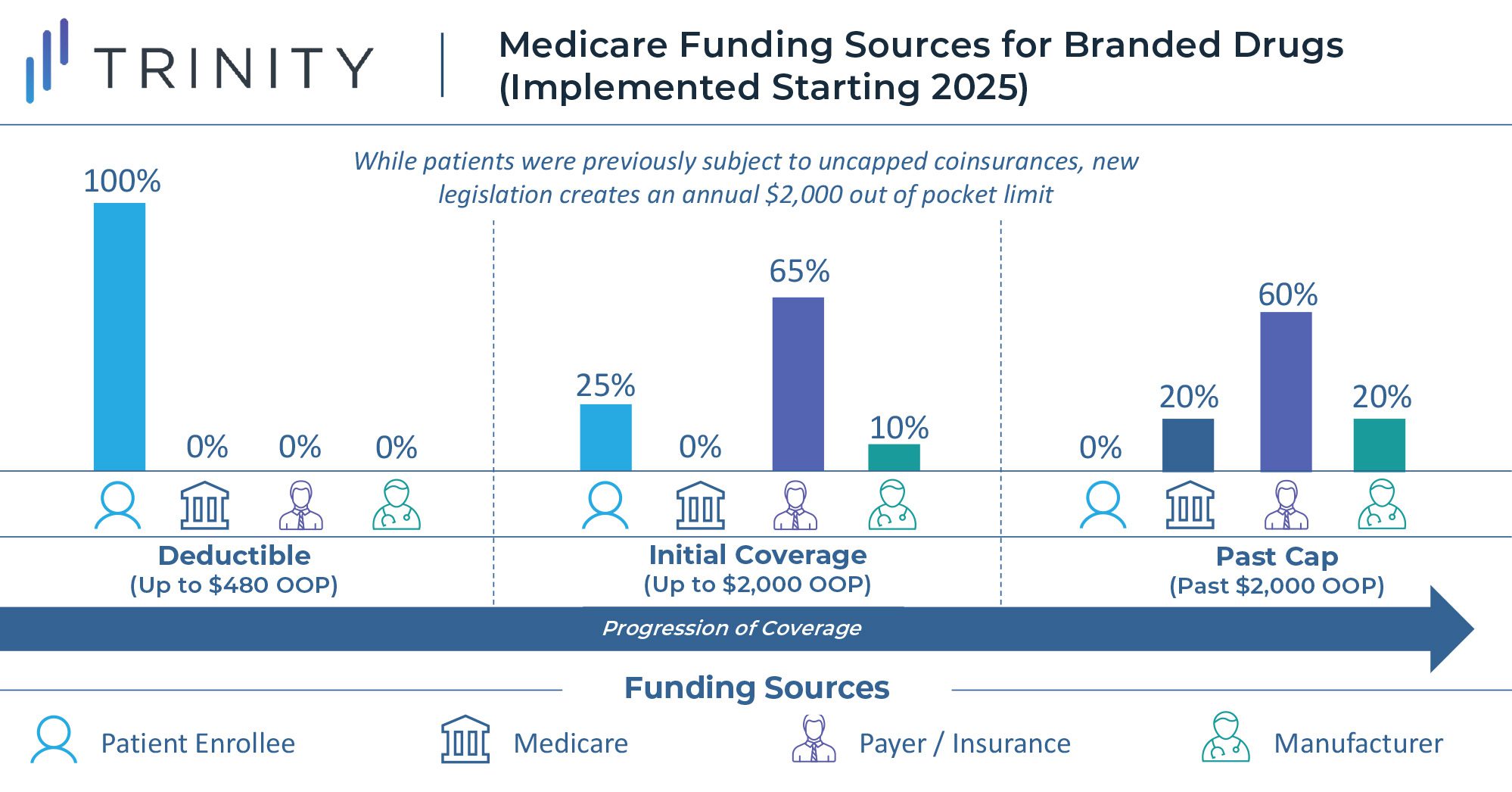

To reduce this burden, the law establishes an annual out of pocket cap of $2,000 for Medicare Part D enrollees, aiming to decrease drug spending costs for the nation’s seniors. Starting in 2025, once a Medicare beneficiary’s annual out of pocket spending exceeds $2,000, out of pocket costs will be eliminated. At this point, branded drugs will be funded 20% by Medicare, 60% by the health plan, and 20% by the drug manufacturer. Any generic drugs purchased past the spending cap will be covered 40% by Medicare and 60% by insurance plans.

Meanwhile, the legislation stabilizes Part D premiums to ensure that these costs are not passed on to seniors. The law further implements a monthly cap of $35 on insulin costs for Part D enrollees, impacting an estimated 3.3 million beneficiaries, and eliminates cost-sharing for certain vaccines. The law initially included the insulin cap for the commercially insured population as well, but this was removed by the Senate Parliamentarian as it violated the Byrd Rule which prohibits setting prices in the commercial market, and Democratic sponsors failed to gain the necessary 60 votes to overrule this decision.

According to the Senior Citizens League, approximately 25% of Part D beneficiaries, or 22 million people, are at risk of exceeding $2,000 in prescription drug spending in 2022, demonstrating the large population that this policy will impact. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that the cap will save more than 860,000 enrollees at least $900 annually.

Industry Impact

In the near term, the Inflation Reduction Act’s most significant impacts to the biopharma industry come in the form of capped out of pocket costs for Medicare patients and the expansion of rebate penalties for price increases that exceed the rate of inflation. The out of pocket cap is a welcome reform given the restrictions on the ability for biopharma manufacturers to directly cover out of pocket costs for Medicare patients as has historically been common on the commercial market. The limit to the ability to raise prices over time will place further importance on the initial launch price of new drugs, and potentially apply upward pressure on launch prices given uncertainties to what pricing over time may look like.

Depending on the specifics of the implementation of Medicare direct negotiation (and ability to withstand legal challenges), the greater impact of this legislation will be felt in the longer term. Future therapies with the potential to drive sustained sales to the Medicare population deep into their lifecycle will be most impacted by discount requirements once they take effect. Today these products may be in the pre-launch stage, leaving manufacturers to determine how to account for downstream discount pressure should long-term commercial success be captured. This long-term discount pressure may once again push launch prices up as manufacturers seek to offset projected lost revenue in the time between peak sales and loss of exclusivity.

Additional strategies to mitigate revenue loss could include agreements with generic or biosimilar manufacturers to avoid having the single source or monopoly designation that makes drugs eligible for Medicare discount negotiations. While this may also lead to revenue leakage, this could be partially offset by licensing agreements that generate new revenue streams. Uncertainties remain on how legislators may try to close loopholes such as these in the future, how the law may impact overall investment in biosimilar and generic development, and what consequences may persist from having differential discount timelines for products approved via NDA vs. BLA.

Conclusion

First and foremost, it is important to note that the Inflation Reduction Act increases access to health services for many Americans by funding premium subsidies for the insurance exchanges established by the ACA and creating an out of pocket cap for Medicare beneficiaries. Stepwise legislation to expand the number of insured individuals in the US continues to benefit the biopharma industry as more patients will be able to receive necessary treatments.

However, the main function of this legislation is to generate revenue for the federal government and reduce drug expenditure in the Medicare program. From a drug policy perspective, this is primarily done by mandating discounts on therapies that carry high Medicare sales deep into their lifecycles without generic or biosimilar competition. Manufacturers may seek to avoid eligibility for these discounts through tactics like those already employed when approaching loss of exclusivity, such as entering structured agreements allowing for limited generic or biosimilar competition. While strategies like this could avoid discounts, yield royalties, and partially offset revenue loss, ultimately these forces will constrain the ability for blockbuster drugs to continue to enjoy peak-level Medicare sales deep into their second decade on the market.

While the narrative around this legislation has been framed to imply that Medicare will now negotiate drug prices, it would be more accurate to describe this as an expansion of statutory discounts with flexibility for the government to seek further rebates for long-lasting blockbuster drugs. While price increases will be constrained, manufacturers retain complete freedom to set launch prices according to the value they ascribe to them without government intervention. The onus to provide value-for-money for medical innovations backed by robust evidence remains squarely on drug manufacturers, and the status quo of free pricing with a system of statutory discounting remains the path forward in the US for the foreseeable future.

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022:

No Room for Negotiation

Authors: Maximilian Hunt, Christian Frois, Rob Albarano, Grace Mock

Special thanks to: Kate Balicki and Ishan Patel

Related Intelligence

Blog

Rise with the waves: France – Accelerating Pricing and Market Access: Two Policies Shaping Pharma’s Future

Executive Summary The latest publication of new reimbursement regulations in the French Social Security Financing Act (PLFSS 2024), coupled with the recent approval of HEMGENIX® through the direct access scheme in France this past December, underline continued efforts in France to innovate its healthcare system. The 2024 PLFSS emphasizes: The direct access scheme is expected […]

Read More

Webinars

2023 NRDL Update: An Ongoing Voyage of Innovation and Accessibility

May 1, 2024 | 12:00 – 12:45 PM ET / 18:00 – 18:45 CET

An additional session will be offered on May 7th at 16:00-16:45 (UTC+8:00) – Asia/Shanghai How can manufacturers strategize for pricing and market access success amidst the evolving landscape of China’s NRDL? As China continues to be a key pharmaceutical market, understanding the latest National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) trends and policy evolvement is crucial for […]

Sign Up Now

White Papers

Evidence Generation in a Post-IRA World

Since the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, the pharmaceutical industry has significantly altered how they approach and plan for evidence generation activities to best support product launches and pricing and access negotiations. Leading life science companies are taking proactive steps to adjust how and when they develop evidence and how they […]

Read More