Japan’s Latest Drug Pricing Policy Updates: Key Changes in 2022 and the Expected Impact

Executive Summary

- A series of new drug pricing reforms came into effect in Japan in April 2022, to encourage innovation and ensure the transparency and predictability of drug pricing in the future

- These include updates to the cost-accounting pricing methodology, an expansion of the scope of the Price Maintenance Premium (PMP), an update to the spillover rule for drug re-pricing and an addition of a new “specific use” premium. Further details are outlined in the graphic below.

Summary of Japan’s Drug Pricing Policy Updates

| POLICY CHANGE | DETAILS |

|---|---|

| Update to Impact of Costs Disclosure Level for Cost Accounting Products |

|

| Expansion of Price Maintenance Premium Scope |

|

| Update to the Market Expansion Re-Pricing Spillover Rule |

|

| Introduction of “Specific Use” Premium |

|

Introduction

In December 2021, Japan’s reimbursement policy panel outlined a series of new drug pricing reforms that became effective April 01, 2022. These reforms aim to encourage innovation, secure stable drug supplies, and ensure the transparency and predictability of drug pricing.

Japan Pricing System Overview

Novel pharmaceutical products aiming to launch in Japan are subject to a rigorous pricing assessment by the Central Social Insurance Medical Council (Chuikyo). Products can be assessed and priced through the Cost Accounting Method, the Comparison Method I or the Comparison Method II depending on the presence / lack of an appropriate clinical comparator and the novelty / clinical benefit of the product. The Cost Accounting method is typically the desired pricing mechanism for manufacturers as it generally leads to the most favorable pricing outcome and is granted to a product when the MHLW deems that there is no existing comparator for the product in JPN.

Products launched in Japan are also subject to price revisions through different mechanisms. One of such mechanisms is the National Health Insurance (NHI) price revisions, where product prices are adjusted biennially (along with off-year revisions) based on discrepancies between the NHI price and manufacturer selling price / wholesaler and provider purchasing price. Another re-pricing mechanism is the market expansion re-pricing, where product prices are adjusted when the product exceeds specific total sales thresholds and / or ratio of actual vs. forecasted sales.

Some of the key policy reforms targeting both these initial pricing and re-pricing rules are outlined below.

Proposed Policy Changes

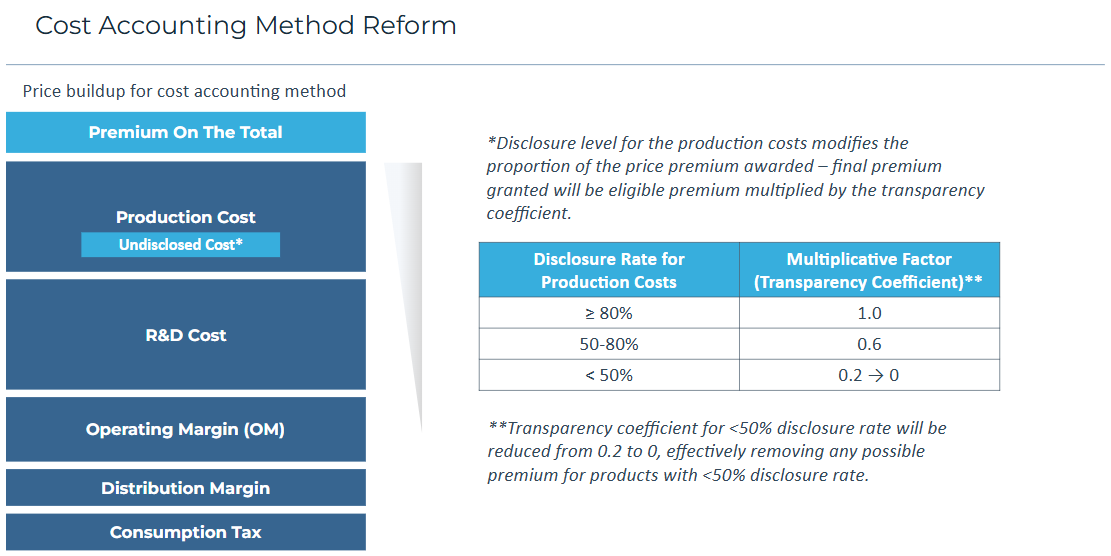

Cost Accounting Transparency Coefficient Update

As previously mentioned, if there is no appropriate comparator for a novel drug at the time of launch, the MHLW will price the product under the Cost Accounting method where the product’s price will be determined based on its manufacturing costs, R&D costs, sales cost, operating profits, distribution cost and consumption tax. Premiums may then also be applied on top of these costs and are adjusted depending on the transparency of the production costs provided. The magnitude of the premium is reduced if production cost disclosure rates are less than 80%, as shown in the diagram below.

To improve price transparency and to ensure the Cost Accounting method captures the most appropriate pricing level, the transparency coefficient for disclosure rates of less than 50% will be reduced from 0.2 to 0, which removes any possible premium for products with low disclosure rates. As well as improving pricing transparency, this change could also be an attempt to further encourage manufacturers to seek pricing via the Comparison Method I vs. Cost Accounting method, which is in line with the recent increasing trend for the MHLW to steer away from pricing via the Cost Accounting method to limit drug prices.

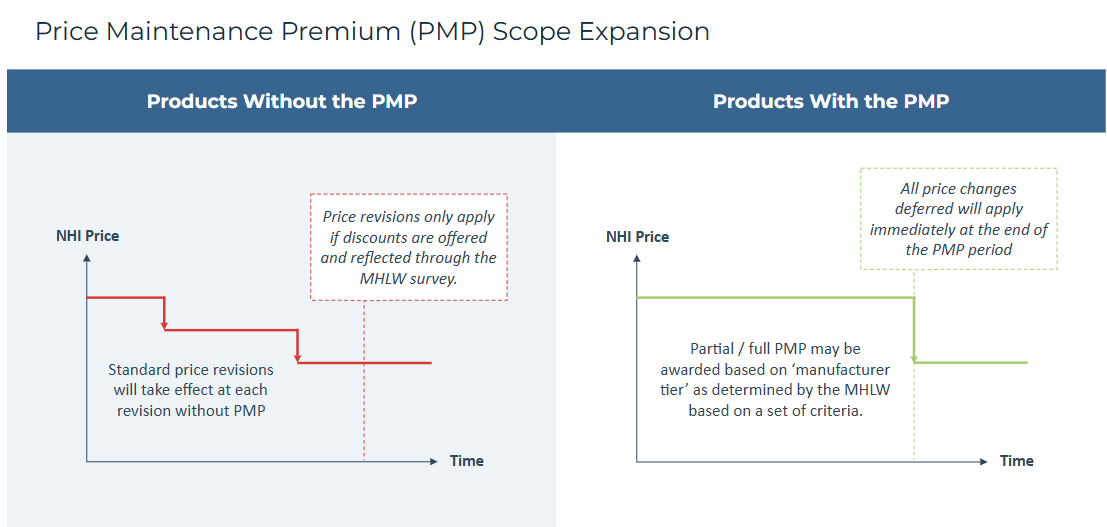

Price Maintenance Premium (PMP) Scope Expansion

The PMP was introduced in 2010 to protect innovative products from NHI price revisions, where the price cuts from the revisions are deferred until the end of the PMP period (which is usually the patent protection period). Previously, PMP was only granted for orphan drugs, products developed through the request of the government, products awarded a premium for clinical value (or an operating profit premium) and products with a first-in-class Mechanism of Action (MoA) with comparative clinical evidence and no alternatives (or products that launch within 3 years of the first-in-class PMP drug with similar efficacy).

In order to incentivize continuous innovation of products and expansion into new indications, the criteria for PMP eligibility will be expanded to include listed PMP-ineligible drugs (i.e., drugs that initially did not receive a PMP) that have added new indications that would have obtained price premiums at launch if they had been approved at listing.

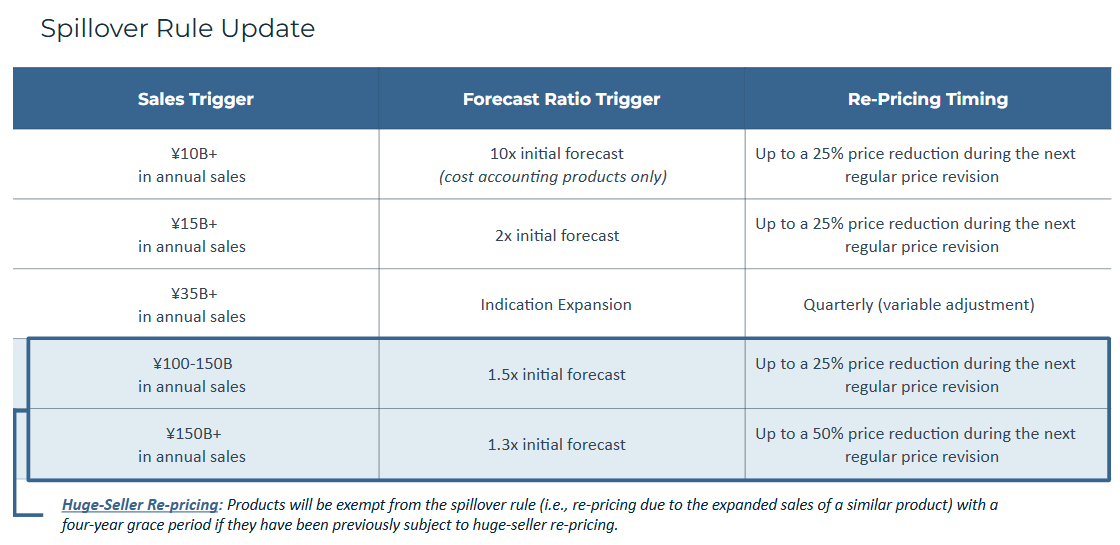

Market Expansion Spillover Rule Update

Separate from the NHI price revisions, a drug may also be re-priced if it exceeds specific total sales thresholds and / or ratio of actual sales vs. initially forecasted sales thresholds. The current “spillover rule” states that market expansion re-pricing is not only applied to the drugs that posted expanded sales to trigger these price cuts, but also to other similar products (e.g., products in the same class).

This “spillover rule” is set to be modified so that products that have been subject to a prior “huge-seller” re-pricing either directly or indirectly because of a similar products repricing will receive a grace period of four years, during which their price will be exempt from any reductions due to spillovers. This exemption will only be allowed once per product.

“Specific Use” Premium Introduction

A new “specific use” premium (特定用途加算) will be introduced, alongside the current innovation, usefulness, marketability, pediatric and sakigake premiums. New products will be eligible for this 5-20% premium if they meet the following requirements:

- The product did not receive a marketability I or pediatric premium

- The product’s comparator did not receive a marketability I or II premium

- The product covers a small market size with a high unmet need

In line with the other outlined changes, the goal of the addition of this new premium is to further incentivize innovation with the reward of greater pricing flexibility.

Other Noteworthy Updates

In addition to the above-mentioned proposed pricing changes, other updates are also being implemented to address the increase in drug spending due to the rising number of high-cost drugs. In the future, if products with forecasted annual sales over 150B yen are approved, the MHLW will immediately liaise with Chuikyo to discuss their pricing methods, whereas currently this only takes place later in the pricing process in order to ensure controlled drug spending.

Expected Impact on Manufacturers’ Pricing and Market Access Opportunity in Japan

The changes to the re-pricing spillover rule, PMP scope expansion and addition of the specific use premium will likely be welcomed by manufacturers in Japan, as these measures provide additional incentives for innovation. These policy changes could also indicate a slightly more favorable environment for products undergoing indication expansion and demonstrating clinical benefit sufficient to award premiums, as well as for products in classes with products that have undergone or are expected to undergo price cuts based on huge-seller re-pricing.

While the changes to the re-pricing spillover rule and PMP scope expansions could be good news for some products, the MHLW will also look to balance such updates through tighter price control in other areas.

As outlined previously, the increased scrutiny of low disclosure rates for the Cost Accounting method is another key update. Though this could encourage greater manufacturer pricing transparency, this would likely have limited impact on products that are expected to achieve a high base price as a result of the Cost Accounting method and are expected to be rewarded a minor premium – manufacturers for such products are still likely to claim high costs with low disclosure rate while foregoing the potential for a premium. It is nonetheless a step in the direction of encouraging greater transparency while further limiting premium potential for those that do not want to disclose their prices, which is in line with how the MHLW has been increasingly looking to curb drug prices in recent years.

Conclusion

The outlined key changes to drug pricing in Japan have the potential to impact both initial product pricing (via the changes to the cost-accounting transparency co-efficient and addition of the specific use premium) and future re-pricing (via the changes to both the re-pricing spillover rule and PMP scope expansion). A number of the updates are good news for some manufacturers, but to an extent they are balanced by other updates which are more in line with the price curbing approach that the MHLW has been increasingly pursuing in recent years.

Other blog posts in this series: